The Office of Digital Humanities at the NEH just released a new study analyzing the efficacy of their Digital Humanities grant program. The response of SUG recipients was uniformly positive and they described the program as “hugely successful”. But a cursory glance of the appendix of projects reveals that for every excellent inPho there are a handful of half-baked digital humanities projects that sadly litter the landscape. The Start-Up Grants were designed as High Risk / High Reward, and so failure is a definite possibility, but it’s been six years since A Companion to Digital Humanities was published and participants in the field are still uncomfortable criticizing the work of their peers and of themselves. As I said on HASTAC last year, if the Digital Humanities is to be taken seriously, then we need to be able to distinguish between success and failure. Everything isn’t successful, even if it’s innovative, just look at Google Wave.

Like many people, I always meant to use Google Wave. The initial beta was only open to select digerati and the press release described a transcendent, synthetic form of communication that would do to email what email did to the telephone. Wave was multimodal, real-time and still grounded in text–which sounds like most Digital Humanities project proposals–and, unlike so many of those proposals, Wave actually got up and running. But last month, Google pulled the plug, and the more I think about this ambitious project, the more I think humanities scholars could do well to learn from Google’s experience.

It’s possible Wave was axed because of the use of a non-compliant Java framework, which would open it up to legal action by Java’s new owners at Oracle, and while this may have contributed to Google’s decision to drop Wave, I tend to think it had more to do with the tension between Wave’s grand potential and its rather middling adoption.

Ambition and feature creep go hand-in-hand

Google Wave was an email and a document and an instant message and more. It integrated video with text and put the whole thing together in a wiki-like editable space. The framework was new and innovative, but it was fundamentally a synthetic project, which is very common in the Digital Humanities. These synthetic projects are easy to envision, but if not carefully considered, they can also resemble a certain meme known as Yo Dawg:

The “Yo dawg” or “Sup dawg” image macro first appeared on the ’chans in early 2007 and experienced a resurgence in late 2008 on Reddit, Tumblr, and other mainstream forums & blogs. It follows a simple format:

Standard: {yo,sup} dawg, I herd you like X, so I put an X in your Y so you can VERB while you VERB

Repetitive: {yo,sup} dawg, I herd you like X, so I put an X in your X so you can X while you X

Abstract: {yo,sup} dawg, I herd you like X, so I put an Y in your Z so you can VERB while you VERB

Now, I’m not saying that Google heard we like videos and wikis and texting so they put all that in an email so we can do all that while we do all that, but I can think of several Digital Humanities projects that consist of simply bolting one concept onto another without any theoretical or technical effort expended to present a unified structure. When Ruth Mostern and I built the Digital Gazetteer of the Song Dynasty, we’d considered also building a web interface allowing search and visualization but decided only to release the raw database, because the web app, while highly visible (and therefore professionally valuable), wandered too far afield from the project’s initial purpose: to build a rigorous and sophisticated representation of medieval Chinese political geography.

Acknowledge when you don’t have an audience.

Even the most tedious academic scholarship has metrics for success based on audience adoption. Sure, your latest monograph on 17th century French medallions may not show up on the New York Times Best Seller List, but if it didn’t even get bought by the UC library system, then maybe that’s a sign that you, too, should move on. In like manner, if you’ve built something that no one is utilizing, then maybe it’s time to phase it out. Which brings me to the most important lesson that Google Wave taught us:

Don’t just wander away from a project, definitively end it.

A colleague of mine pointed out that the Valley of the Shadow Project had a definitive end and that now the library has the (not easy) task of maintaining it as a finished work. This is decidedly not the norm with Digital Humanities projects. Even the most superficial survey of “current” Digital Humanities projects will reveal that many are vaporware or abandoned. The lack of a definitive end product short-circuits the capacity for outside scholars to review the work of their peers and determine its quality. The field cannot be taken seriously as long as this remains the standard practice of its participants.

Reuse, Reduce, Recycle

I started this post by writing that everything isn’t a success, and I know that one argument against that is even in failure there are lessons to be learned, methods and technologies developed. Google is opening up more of the source code and, we can be assured, folding into other projects lessons and code that they may not be making public. But these steps, whether it’s turning over created data to library curation or making public the code underpinning your Digital Humanities projects, will be hindered or completely unavailable if you cannot acknowledge that your project is over. There are three probable results for any valuable technical or methodological assets of failed Digital Humanities projects that fail to acknowledge their failure: Either they’re distributed arbitrarily in a piecemeal, shadow economy, or they’re only publicly released when they’re outdated and the value has significantly declined, or they vanish and all the work and effort and thought that went into them might as well have never occurred.

One of the most common responses about the Digital Humanities SUGs was that just winning the grant established credibility for the scholar in question. Credibility cannot rest solely on the ability to get grants. The academy has a long tradition of peer review in the establishment of scholarly credibility, and though peer review is problematic, it is focused on results and on the ability for the scholar to properly describe their results, even when the original goal was not achieved. We cannot achieve that ability to review works unless the creators of the work can define its completion. And we also cannot place value on works unless we can acknowledge failure when it occurs. Google Wave was a failure, but Google isn’t. Likewise, digital humanities projects can be failures without the Digital Humanities being a failure. It’s time to acknowledge that.

Update: I bit the bullet and did my part for memedom.

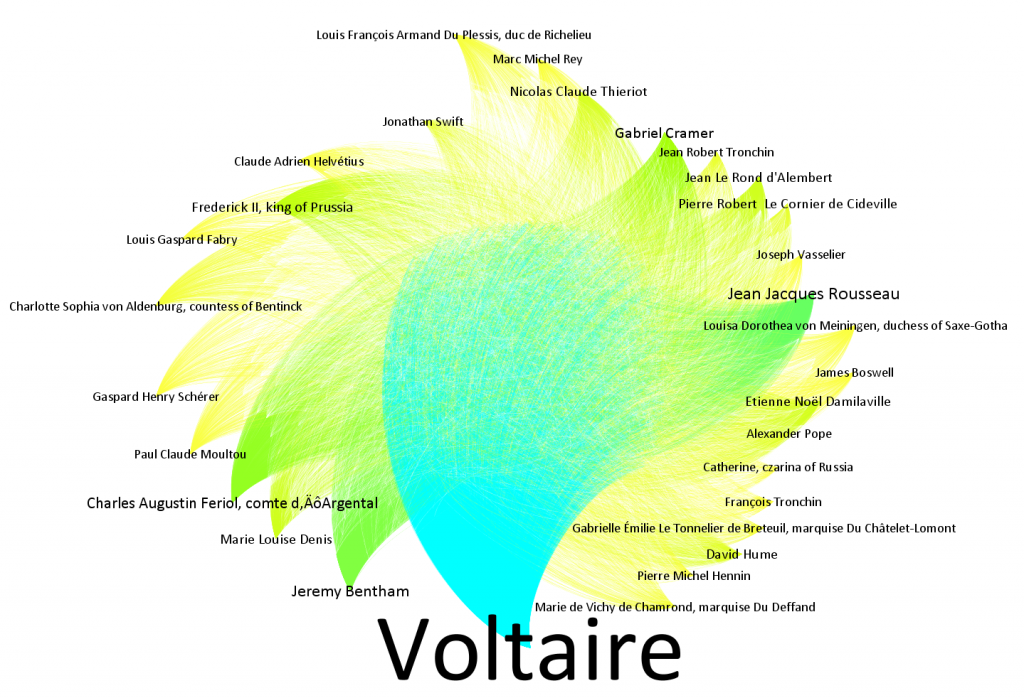

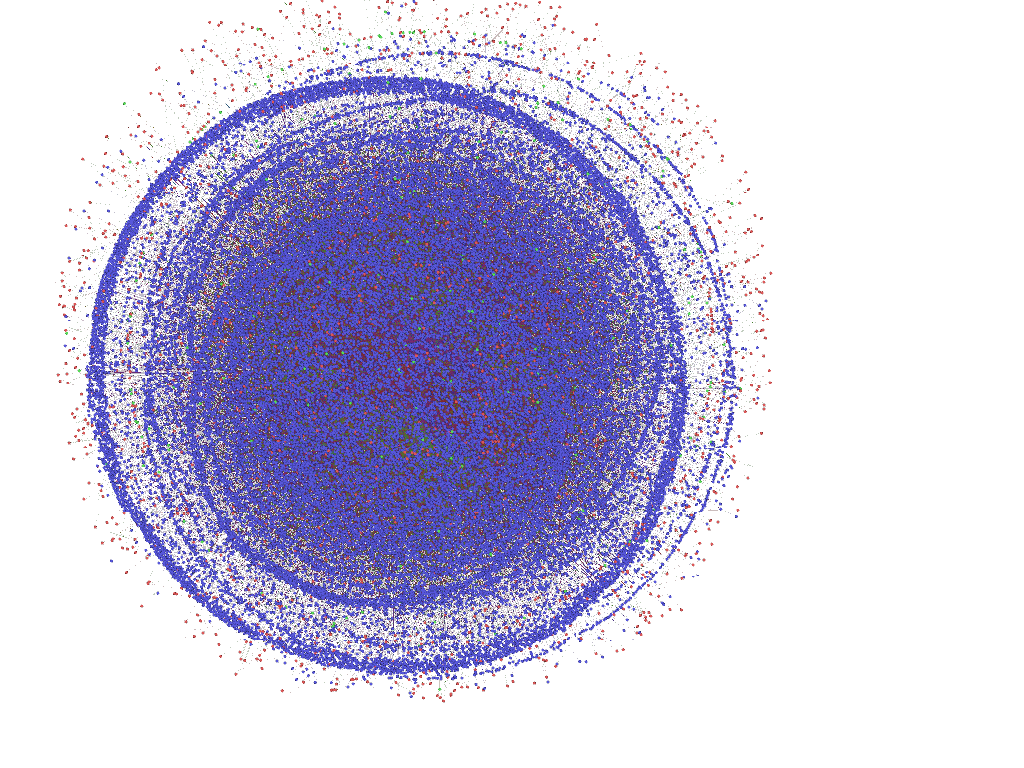

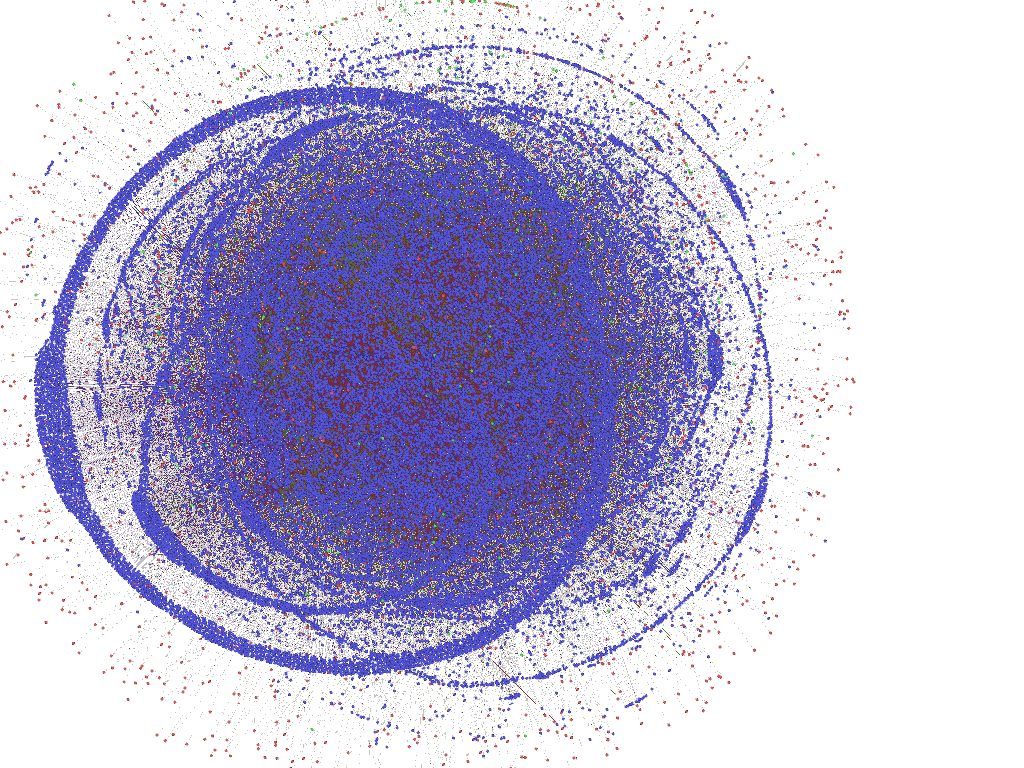

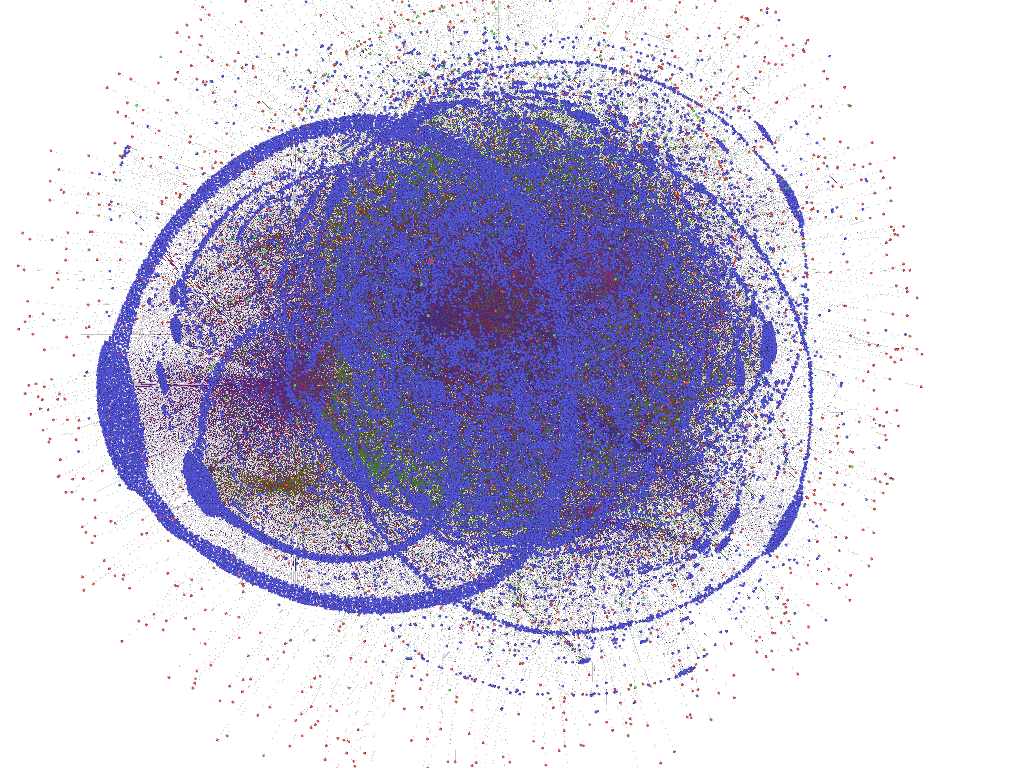

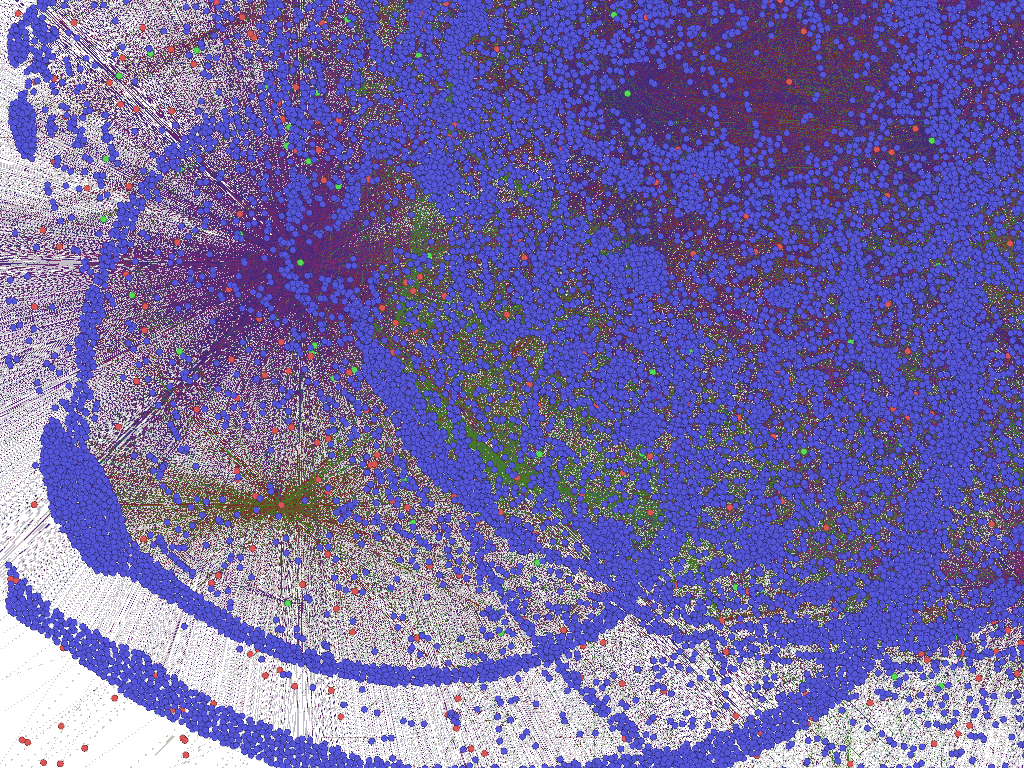

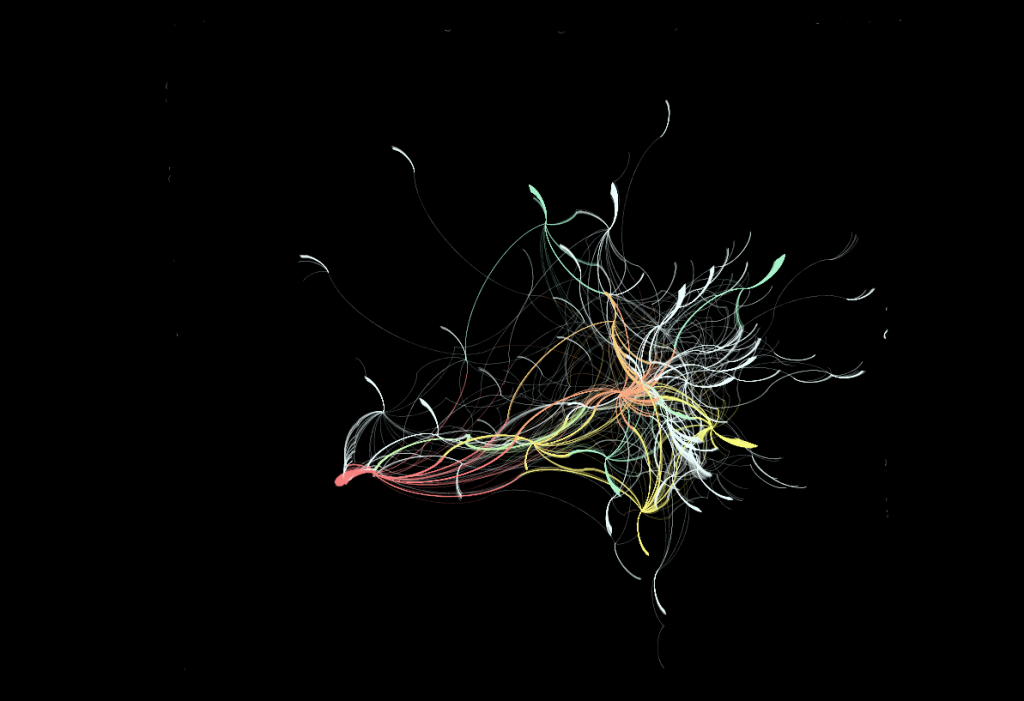

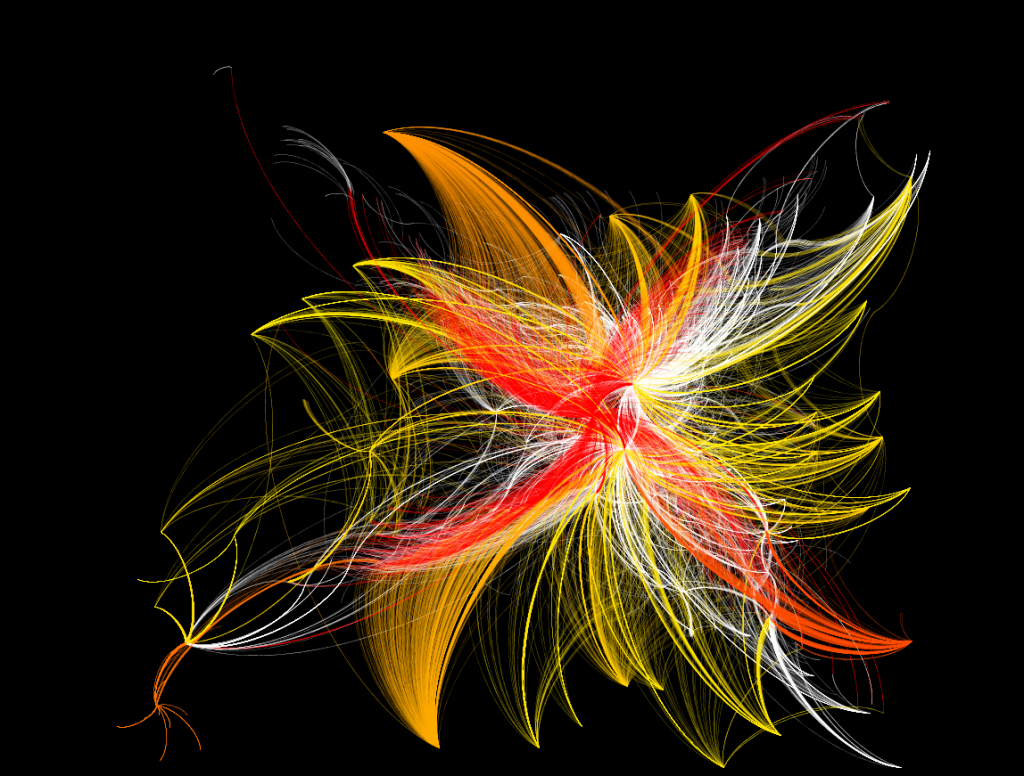

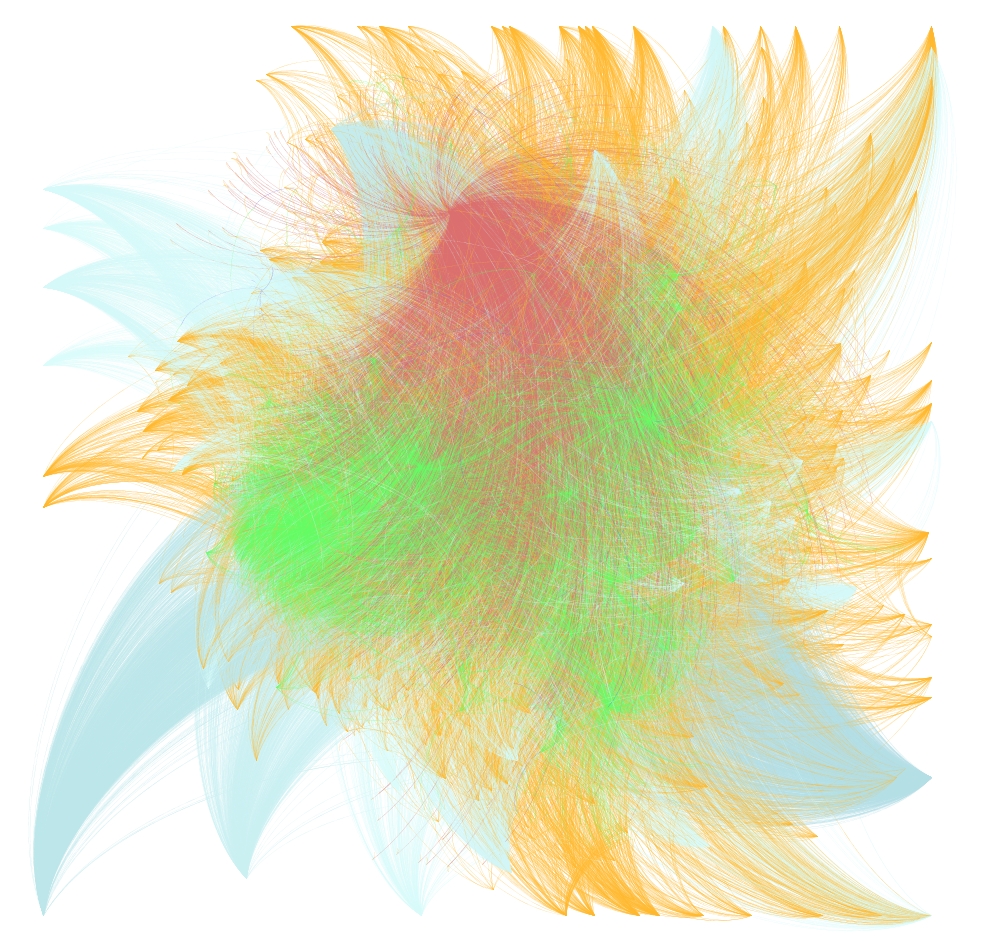

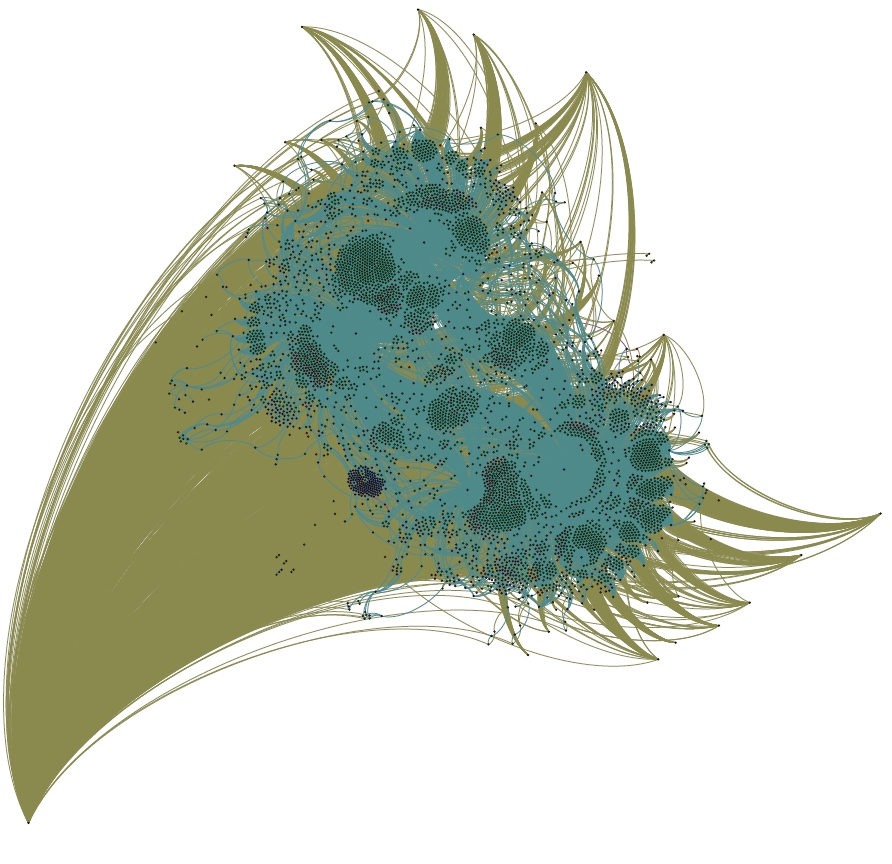

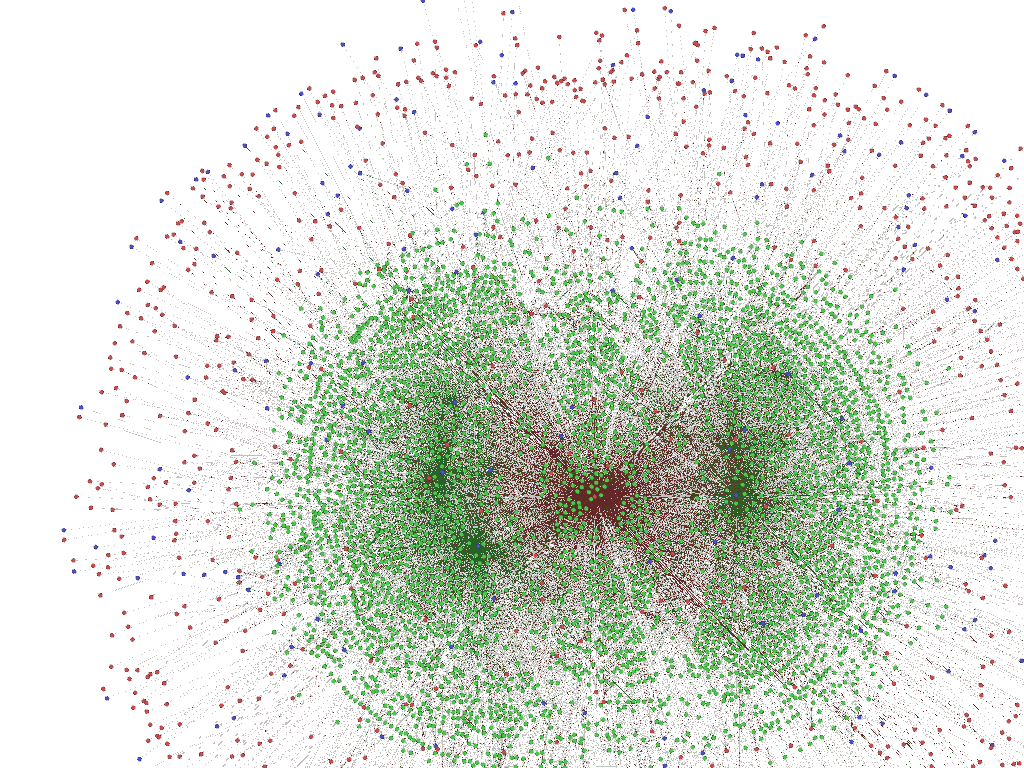

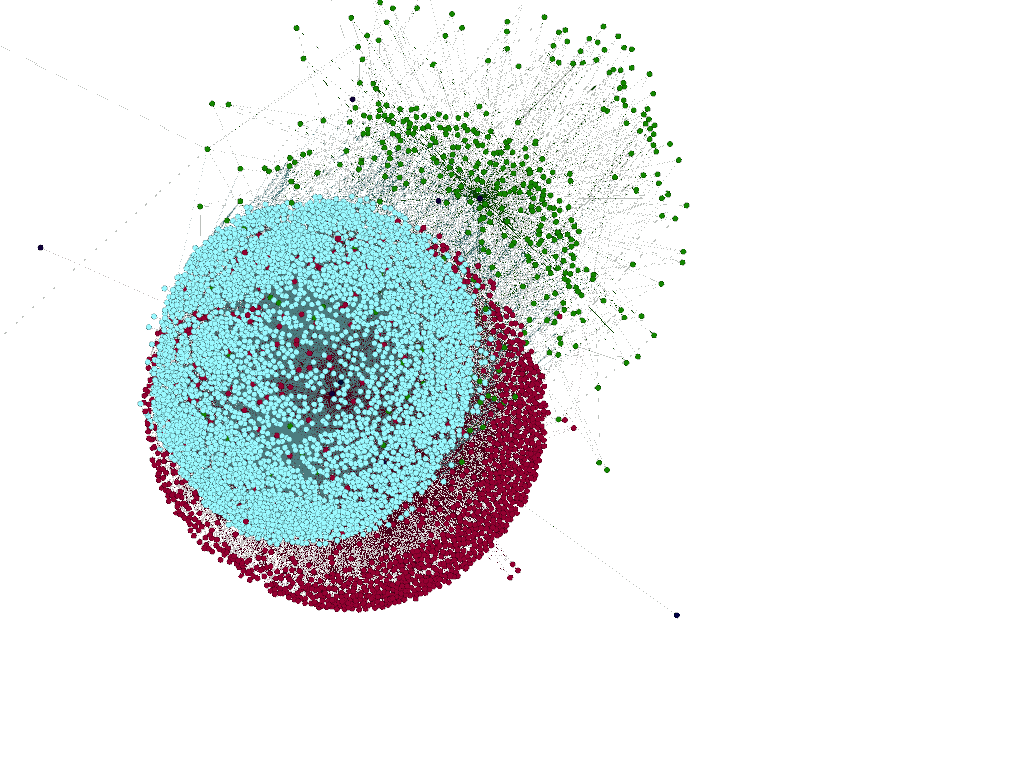

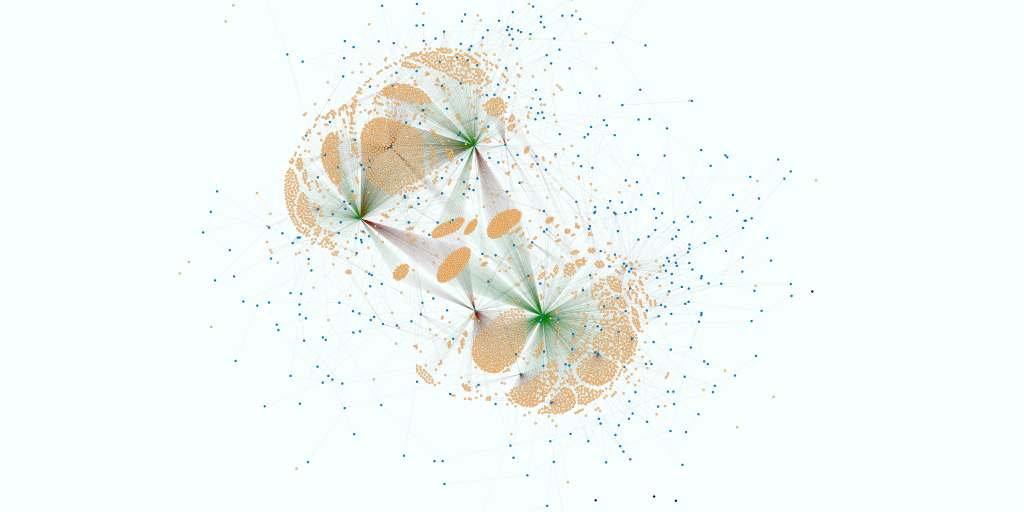

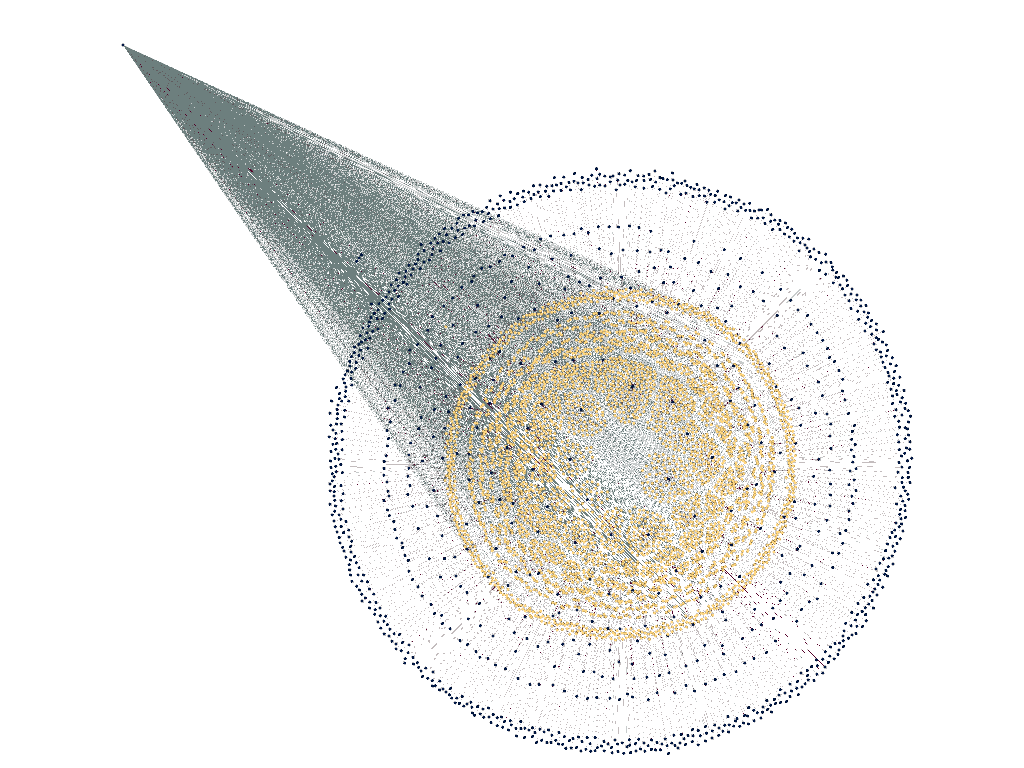

And, finally, the early phases of Voltaire’s network in the process of self-organization:

And, finally, the early phases of Voltaire’s network in the process of self-organization: