I’ve been working on research-oriented digital humanities projects ever since Ruth Mostern decided to pursue a database version of Hope Wright’s An Alphabetical List of Geographical Names in Sung China in 2007. The goals have varied–sometimes the purpose was to explore data and corpora and other times the intention from the very beginning was to produce an interactive publication. But regardless of the end result, my experience of collaboration between someone who was technically more savvy (myself) and someone who was deeply embedded in their discipline (generally a tenure-track faculty, sometimes a grad student or librarian) has generated a few lessons on how collaboration in digital humanities projects can succeed, and how it may not.

There’s been much written about collaboration and the growth of collaborative projects involving humanities scholars, including the excellent Collaborator’s Bill of Rights as well as rumination on what dangers collaboration may pose, such as my own article in JDH1-1. My writing here is focused on a more specific kind of collaboration then the general phenomenon covered by these. My work typically involves direct, long-term collaboration with a an individual scholar over a long but fixed period focused on a single project with some kind of defined end product. This is in contrast to the large-scale structured lab support provided by entities like the Scholar’s Lab at UVa as well as the more generalized support provided by a typical post-doc attached to a project, lab, or scholar. I can’t say if my experience is typical or not, though I’ve had the opportunity to see a few different support situations here at Stanford and at various universities, and it would seem that what follows has at least broad applicability.

Staff is an absurd category, alt-ac is a step in the right direction

Almost exactly two years ago, I offered up a tripartite view of academic production that presented librarians, faculty, and undergraduates as occupying different areas of a data (or content ecosystem) and that digital humanities represented a blurring of the boundaries between them. As much as digital humanities is defined by information visualization or computational approaches, it is also defined by faculty building collections, librarians doing research, and students wandering free between content consumption, content creation, and content management. Of these three groups, it is the the definition of a modern librarian, and by extension a university staff member in any unit supporting research, that is the most difficult to figure.*

The main reason for this is that there’s a professionalization of staff positions that does not exist in the other two groups. Anyone who has worked with undergraduate and graduate research assistants knows that their effort and engagement is not demanded but negotiated. Such is obviously the case with faculty working with other faculty. Staff, on the other hand, with their various layers of management and leadership, are service providers embedded in a more formal hierarchy. This distinction can be the source of tension in situations where faculty, students, and staff are working together to advance digital humanities scholarship.

The development of the concept of alt-ac as a kind of staff that engages more visibly in research has helped to advance our understanding of what staff can do in digital humanities, but I find many of the arguments wrapped up in concepts of fairness, labor equity, and social justice. All of these are important to me, but even a cursory understanding of how the academy as a whole has completely failed adjunct faculty will remind us that such lines of argumentation will fail to resonate.

Collaboration is more than good, it’s necessary

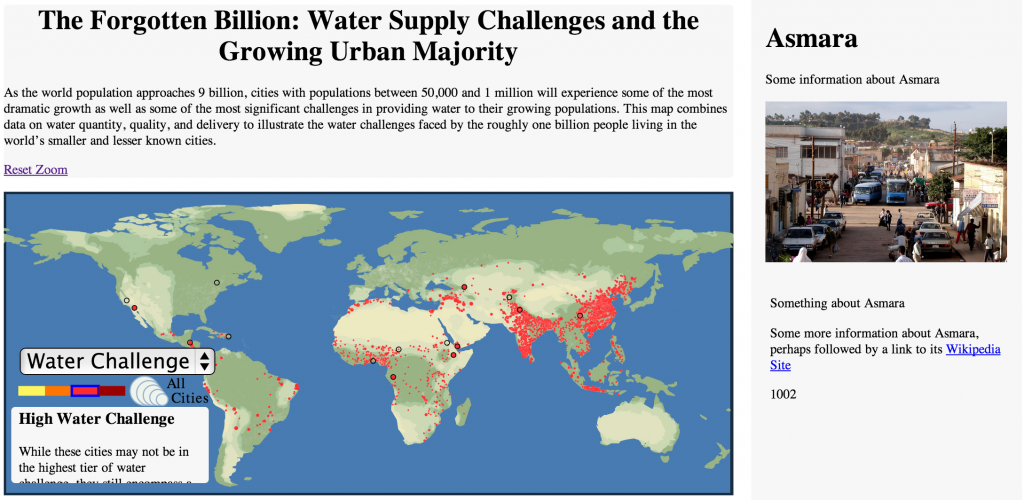

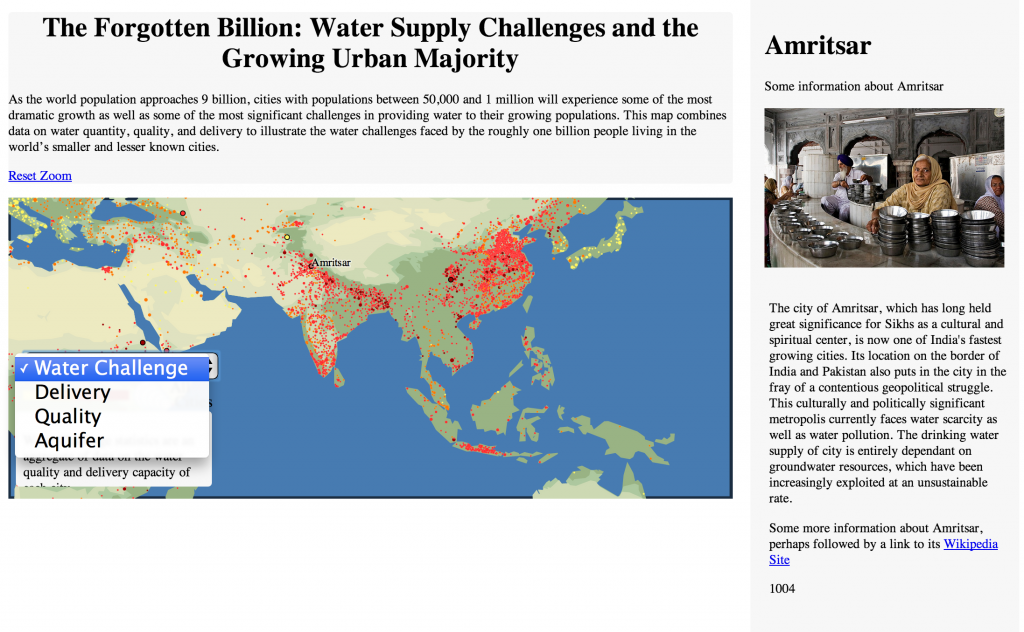

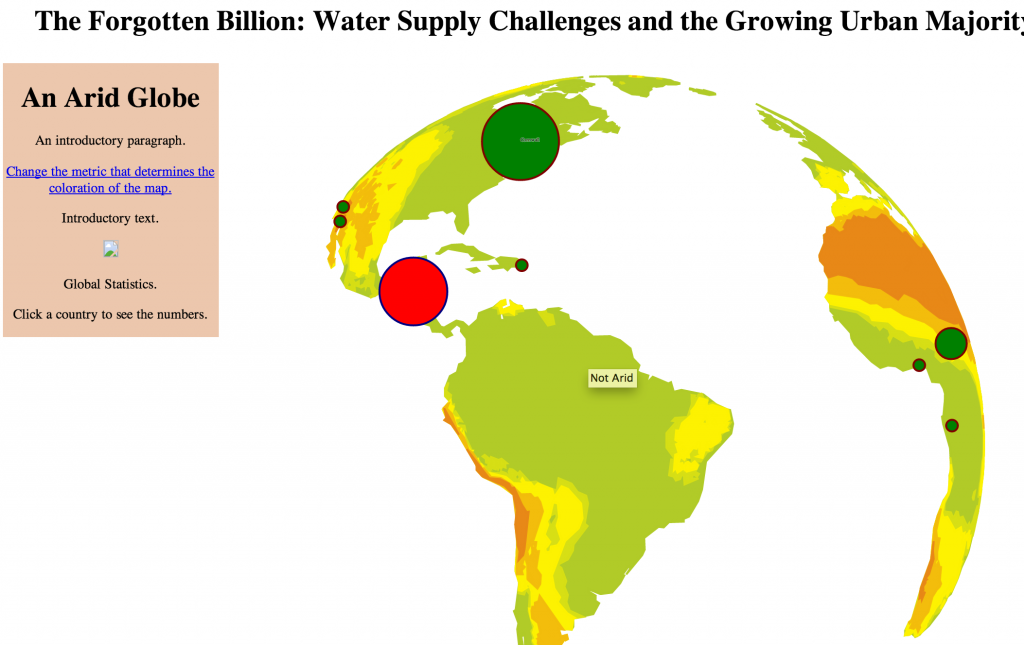

Fortunately, there are other reasons to foster healthy collaboration where faculty and alt-ac staff are on equal footing. The first and most obvious is that someone with expertise in the tools and methods being deployed in digital humanities research will by necessity take part in establishing and furthering the research agenda. In my experience, the most effective digital humanities work is done when a scholar has an innovative, sophisticated agenda that can be furthered by application of computational methods, digital publication, and/or the host of tools now available for analysis and representation. But that line of inquiry has, in every project that I’ve been part of and every project that I’ve been exposed to, mutated and grown to include more sophisticated and more methodologically-rich concepts provided by the nominal technical experts. There may come a time when research and publication of the kind being done in digital humanities is so well-established, or the techniques and methods so generally understood, that this is not the case, but until that time comes, you want a peer collaborator, not an employee.

The second reason for peer collaboration is because they’ll be honest about what can and can’t be done. Imposter syndrome is on full display in alt-ac, and most everyone I know in a position like mine who I’ve had a chance to read or work with is highly critical of her own capabilities when it comes to programming, statistics, and formal types of analysis. But many of us have been doing this kind of thing for quite some time, in a variety of ways and quite rigorously. I was creating data models to represent complex definitions of place back when George W. Bush was president. Despite the common protests of various digital humanities facilitators (for lack of a better term) they typically have the experience and expertise, or the awareness of channels to discover it, to be able to provide a scholar with a good indication of whether a line of research will be successful or not. And, critically, they won’t assume that the explanation would be too difficult for that scholar to understand.

The third reason is more cold-blooded, but long proven here in Silicon Valley: if you can’t pay a person what the position should entail, you need to entice them with ownership. I work on digital humanities projects like someone does at a start-up, including long hours and during periods that are nominally not designated as time to perform such work. While I was on vacation for a week last year, I finally had enough time without meetings to nail down the route-finding code for ORBIS. I didn’t do this because I was afraid of losing my job, quite the opposite. I did it because my name was on ORBIS, both literally and figuratively given the visibility of my work on the project. Because I’m invested in the projects I work on, it provides the same incentive that stock options do. If I can successfully complete a project that is high-profile and sophisticated and lauded as an advancement in the field, then the professional benefit more than makes up for the extra time that I spent to make it work.

The kind of investment and effort necessary to develop the innovative research and publication practices for these projects cannot be afforded by your typical scholar with a typical grant. The only way you can defray that cost is to provide some level of ownership of the creative process. That means something more than just a person’s name prominently displayed on a website, or co-authorship of a paper, or casual platitudes during a presentation about the cast-of-thousands necessary to build a thing. It means partnership and peer interaction.

Digital humanities scholarship continues to be a process of discovery rather than an established practice. I’ve written about Interactive Scholarly Works, and I consider this to be an emerging genre, but it has not yet emerged. There is no established blueprint for an ISW that some research can be molded into. Neither is there a “right” way to engage with humanities topics using the many other digital approaches available. To get there, to provide those first examples of what will one day, presumably, become patterns that can be stamped out in professional, assembly-line fashion, we in the library need to provide support for ambitious humanities scholars that want to pursue innovative new research, and we also need to be clear that the only way it will work is with real, healthy collaboration.

* Maybe I just think that’s the case because I work in the library, though when I introduce myself as a librarian I get laughed at by faculty and “real” librarians (in a good-natured way, mind you).

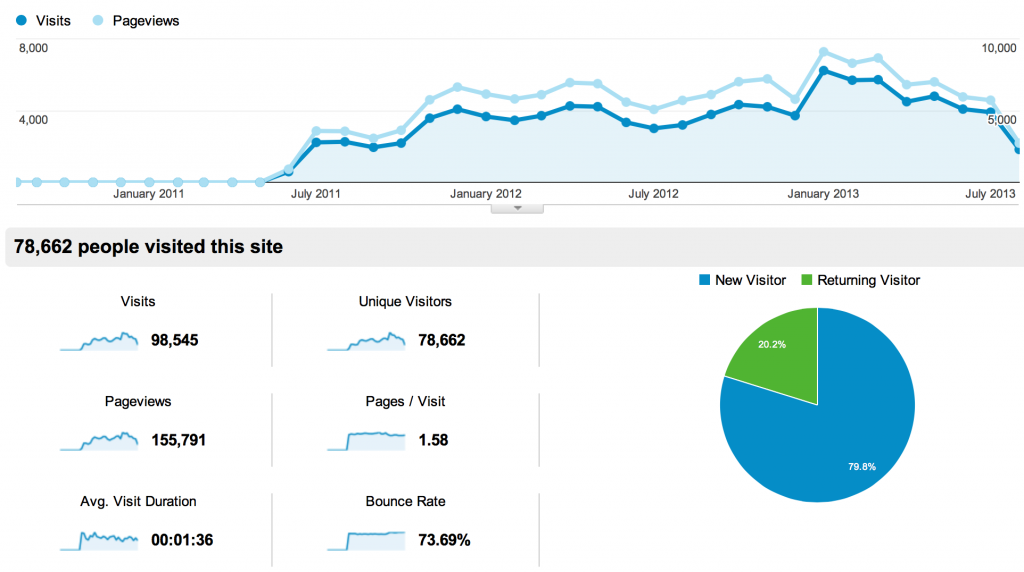

It was exciting to find out that I had 3000 visits a month, and later seeing that grow to 5000-6000. Not exactly big numbers for the Internet, but pretty good for a WordPress site where the closest thing to a cat picture was a grainy shot of Richard Stallman.

It was exciting to find out that I had 3000 visits a month, and later seeing that grow to 5000-6000. Not exactly big numbers for the Internet, but pretty good for a WordPress site where the closest thing to a cat picture was a grainy shot of Richard Stallman.